Illiteracy Is A Policy Choice, by Kelsey Piper in The Argument

There Are No Miracles in Education, by Freddie DeBoer

Is Mississippi Cooking The Books? by Karen Vaites & Kelsey Piper in The Argument

Emily Hanford’s Sold A Story podcast

Small-Group Reading Instruction Is Not as Effective as You Think, by Mike Schmoker & Timothy Shanahan in Education Week

6 out of 10 Kids Use Their Smartphones Between Midnight & 5am—TikTok @eduleadership based on Jean Twenge’s book 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World—coming soon to Principal Center Radio

Full transcript:

Welcome to the Edueadership Show. I’m your host Justin Baeder, and in this episode we’ll talk about the “Southern Surge” and specifically the “Mississippi Miracle.” We’ll talk about some smart ways to use small groups, and why overusing small groups can actually reduce learning during the literacy block.

And we’ll talk about what happens when kids plug their phones in in their rooms overnight. Let’s get to it.

First up, in a new publication called The Argument, journalist Kelsey Piper argues that illiteracy is a policy choice, and she in particular takes to task her home state of California for falling behind, and especially falling behind the state of Mississippi.

She says, in a lot of cases, you would actually be better moving from California to Mississippi to attend the excellent public schools there. And what she’s talking about is a set of policy choices that Mississippi has been making for more than a dozen years now that have caused their reading performance, specifically on fourth grade NAEP, the nation’s report card, to just go up and up and up.

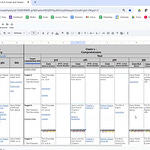

And you can see on this graph that Mississippi has passed the national average. It has passed California. California has gone down. The national average has gone down. Massachusetts has gone down. And Mississippi may soon eclipse the reading scores in Massachusetts as well.

And what she points out here is that Mississippi is spending a lot less than states like California and Massachusetts and getting durably superior results. This is not a fluke. This is not something that just happened one time.

And this is not a test that can be easily gained. There is something real here that Mississippi is doing. And we’ll talk about what that is. And unsurprisingly, part of the story is phonics.

You have no doubt heard the Sold a Story podcast from Emily Hanford, where she goes into the importance of phonics and explains why phonics is often overlooked and under emphasized.

And there’s a huge opportunity there, certainly around phonics, but Kelsey Piper’s article in the argument identifies three factors that go beyond phonics. The first of which is state level mandated or strongly suggested and very well-supported curriculum for teaching literacy that is based on the science of reading.

And in the states that are being the most successful, which especially are the southern states, Tennessee, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, the emphasis on curriculum can’t be overstated. The states are getting involved. They’re not leaving it up to individual teachers or individual districts.

And they’re saying in sometimes fairly heavy-handed ways, this is what you need to be doing to ensure that all students learn how to read. And those guidelines tend to be fairly well aligned with the science of reading.

The second thing that they’re doing at the state level is providing in-depth teacher training on the specific curriculum that teachers are being provided. So there’s a lot of opportunity for teachers to learn how to teach this curriculum effectively.

And then the third piece is accountability. And this one, you know, people would like to believe that that’s not necessary, that it’s not helpful, but it seems to be that there needs to be some accountability, especially for adults to make sure that students get the support they need.

And one interesting policy that’s been getting a lot of attention this year is third grade retention. The idea that you can’t promote a student to third grade if they cannot read, if they cannot pass a particular reading assessment. And the explanations that I’ve seen for why that works have to do with adult behavior, that when adults are not allowed to pass a student on to the next grade, they realize the consequences of retention are pretty dramatic. So they do whatever it takes. They pull out all the stops in order to get those students up to where they need to be in reading.

Now, despite the ample evidence, despite the long-term trajectory of Mississippi in terms of reading scores, there are skeptics. And one of my favorite skeptics to read is Freddie DeBoer, who has been a testing expert, who has been a critic of education. And he has argued for a while that education essentially doesn’t work, which I don’t agree with.

But I do agree with some of his specific points. He says, you know, we’re not really going to close achievement gaps and we need to be very suspicious whenever we see big gains in a short period of time. And he really dismissed Kelsey Piper’s piece about the Mississippi miracle in terms of just his general observations about how often these things don’t pan out, right? There were various turnarounds that on closer examination seemed to disappear or that seemed to not scale.

And yet in this piece, he doesn’t really look at what is different about the Mississippi situation and about the southern surge, specifically that we’re looking at NAEP data and that we’re looking at it over a 12 or 13 year period. We have very long term data now that Mississippi is actually doing much better.

And when we look at what Mississippi is doing differently, it makes sense. So I think there are no miracles. You know, that may be true on its face value, right? There are no miracles here. There’s only hard work, but there are things that work in education and we need to do more of them.

He says in his skepticism in this article, the odds are very, very strong that eventually it’ll turn out that students in Mississippi and other miraculous systems are being improperly offloaded from the books or out of the system altogether. And this will prove to be the source of this supposed turnaround. That’s how educational miracles are manufactured, through artificially creating selection bias, which is the most powerful force in education.

And I think he is right that selection bias is a very powerful force in education. But you don’t have to take my word that that’s not what’s going on here, because Kelsey Piper teamed up with literacy advocate Karen Vaites to write a follow-up piece rebutting the idea that Mississippi is somehow cheating on NAEP, that they are getting students off of the testing rolls to artificially inflate scores.

So they go into quite a bit of detail in this follow-up article, and specifically talking about retention, there was some concern that maybe students were being retained so they wouldn’t be tested in fourth grade. If you retain a third grader, then they don’t get tested the next year. But there were a lot of ways to check that and ways to see if there’s any funny business going on in Mississippi.

And the authors say, before a student is retained, he or she will be screened 12 times across four grades using a quality screening tool approved by the state. Well-trained teachers will have quality lesson materials and they will know which students need extra support. It’s a system set up to work so that very few students need to be retained in third grade, which is exactly what happens.

So I think this holds up pretty well. I think we will continue to hear a lot more about the Mississippi Miracle and the Southern Surge more broadly. And other states are using different approaches that shed additional light on what is working, especially around building knowledge. So stay tuned here on the Eduleadership show for more on that story.

Next up, in a powerful op-ed in Education Week, Mike Schmoker and Timothy Shanahan argue that small group reading instruction is not effective as you think. And they’re specifically taking aim at the idea that core instruction, that Tier 1 instruction that ordinarily would be provided to the whole class, should not be provided in small groups.

And their fundamental argument here is that when you deliver your main instruction in small groups, you’re cutting your time by, you know, however many groups there are. If you have four groups, well, then you’re eliminating three fourths of the instructional time that each student receives because when they’re not working with the teacher in a small group, they’re doing something that is probably less productive. They’re not learning as much. Maybe they’re doing something that is easier and not really challenging them and giving them the intensive support they need.

And they don’t at all argue against small groups for intervention. They don’t at all argue against small groups working with a tutor or a specialist.

What they’re arguing against is spending the entire literacy block in small groups, which I have found to be quite widespread based on the comments I’ve seen on TikTok. They say, given the stakes, we must ask, is the small group model truly superior to whole class teaching for either reading or foundational literacy skills?

Alas, no, despite recent claims that the science of reading requires small groups. Though small groups can be effective in certain circumstances, any advantage is wiped out by the model’s drastic reduction in the amount of instructional dosage. And Mike Schmoker in particular has been talking about dosage for a very long time.

And he argues that we have a lot of opportunity to improve in this profession by simply teaching more, by fitting more in and not allowing ourselves to waste time with things like small groups when we could be using whole class instruction just as effectively.

They also talk about some of the downsides of attempting to differentiate, especially when it comes to core tier one instruction. Differentiation has not been such a good idea for guided reading, they say. As John Hattie has demonstrated in his meta-analyses, differentiated instruction is less effective than providing the same treatment for all students. It denies struggling students the opportunity to engage with challenging material and texts as they fall further and further behind. In this way, small group differentiated instruction is especially hurtful to the poor and underachieving students who most need effective teaching.

And again, I think the opportunity here with small groups is to use them for intervention, to have students work with an interventionist, with a reading specialist, with a tutor, with someone who can provide more, not replacement instruction that is taking them away from that core instruction.

Lastly, I wanted to share with you some insights from my recent interview with Jean Twenge, who will be featuring in an upcoming episode of Principal Center Radio. I sat down with Jean to talk about her book, 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World, and I wanted to share just one thing that I took away from that book. Let me know what you think about this. a shocking six out of ten kids use their phones between midnight and 6 a.m when kids go to bed with their phones they don’t really go to bed and even if they do go to bed they wake up in the middle of the night and get on their phones either to text their friends or because their friends are texting them or they’re calling them

Lots of kids are apparently up in the middle of the night doing who knows what. And the best case scenario is that they’re just talking to their friends. It gets worse from there. But as Jean Twenge says in her new book, 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World—I just talked to her for Principal Center Radio and we’ll get that interview published soon—as she says... One of the biggest risks, even if nothing bad happens, is that kids will simply not get good sleep and sleep is linked to lots of things like you’re much more likely to be depressed and anxious if you are not getting enough sleep.

And if kids are going to bed with their phones in their rooms, they are not going to get enough sleep. And the average age now of getting a cell phone is 10 or 11, not 14, not 15, not 16. 10 to 11 years old. So even in elementary school, we have kids who are on their phones between midnight and 5 AM when nobody should be on their phones. Everybody should be asleep. Kids are texting each other. Kids are calling each other.

And we as adults have to be the ones who say, this is one of our rules. This book is called 10 rules to give your kid, not suggestions, not things to talk about with your, yes, talk about them. but they need to be rules that come from adults because we need to make sure that our kids are not only safe, but that they’re also getting a good night’s sleep. Let me know what you think. So watch for my interview with Jean Twenge coming soon to Principal Center Radio.

And if you’re not already subscribed to Principal Center Radio, you can find it on Spotify, YouTube, or iTunes, or whatever your favorite podcast app is. That’s it for this episode of The Eduleadership Show. I’m Justin Baeder, and I’ll see you next time.